Movie review – Minari

Review by: Raghav Raj

Directed by: Lee Isaac Chung

Rating: 9/10

Right from the very beginning, Minari feels utterly, unmistakably entrancing. It is shot in warm, gentle hues by cinematographer Lachlan Milne, who fills the screen with these muted oranges, lush greens, and rich, earthy browns. These colors are met with woozy, contemplative scoring from Emile Mosseri, whose strings and horns drift achingly through the loping Arkansas plain, following the Yi family as they reach their destination. It all moves in a gentle swirl, finally coming into focus at the sight of their new home in the rural depths of the Ozarks.

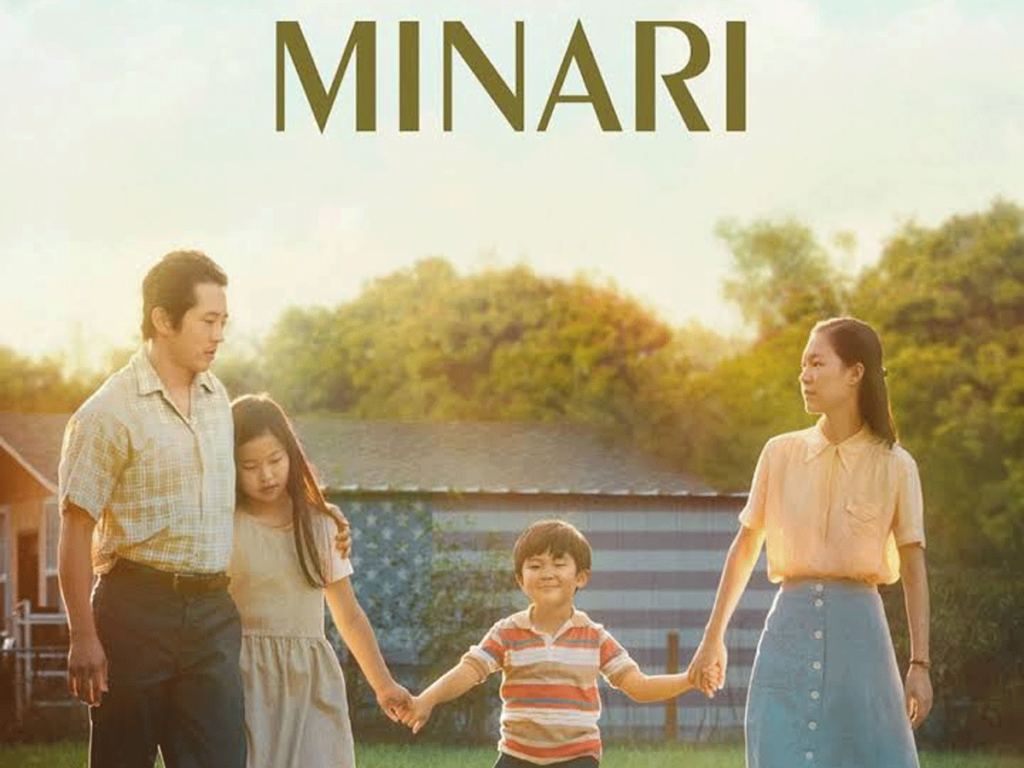

It is at this point that we begin to understand the layers of writer and director Lee Isaac Chung’s semi-autobiographical story, one that draws back to his childhood upbringing in the 80’s as part of an Asian American family in rural Arkansas. The Yi family patriarch, Jacob, has uprooted his family — a wife named Monica and his two kids — from California to rural Arkansas to follow his dream and make something of his own from a plot of land. His wife views this land with nothing short of resentment; her kids see it as a playground to explore and discover.

With this plot, what unfolds over the course of Minari is something revelatory, a truly moving story where family and culture intersect with the prototypical American Dream, embodied by Jacob and all his contradictions, as a man who feels lost and free all at once. Jacob is given a more profound sense of depth by the utterly exceptional Steven Yeun, whose presence is just so magnetic and subtly earnest that you can’t help but root for him and his bullheaded dream, even if it comes in the way of his family.

The family, it should be noted, isn’t without its own subtle interplaying characters. Everyone here turns in a great performance, from Han Ye-ri playing Monica with this remarkable empathy, to Noel Kate Cho’s Anne serving as the more grounded foil to her free-spirited younger brother, David.

Much has been said about little Alan Kim’s performance as the youngest member of the Yi family, but it just has to be stressed how remarkably authentic his actions feel. The conflict and culture clash that ensues when his freewheeling, cursing, and card-dealing grandmother Soon-Ja (Youn Yuh-jung, who rounds out the ensemble cast marvelously) arrives is utterly charming and downright precious to watch play out.

The interactions between the pair offer a profound sense of levity and humor amidst the moments of heartbreak, disconnect, and tragedy that often fill Minari, but what Chung is so great at doing here is keeping everything cohesive in a way that feels deeply authentic. The film manages to avoid the sort of aching sentimentality that lesser films would all too eagerly mine for strong emotional reactions, instead choosing to develop patiently and earnestly through these stark, profoundly intense moments.

The result of all this is something that I genuinely can’t help but marvel at. Minari is just an utterly masterful work of cinematic realism, one that’s unflinching and beautifully poetic, molded in the vein of predecessors like Truffaut and Ozu while still feeling wholly, utterly remarkable. This is, quite simply, a masterwork of empathy, finding something extraordinary in redefining the ordinary American dream.