Aditi Varman | The Chronicle

For Masons Historical Society, history doesn’t just sit on shelves- it’s brought to life. On October seventh, the Rose Hill Cemetery walk transformed the graveyard into a stage, bringing the town’s most suspenseful moments to life. From catastrophic events like murders and robberies to blazing fires that reshaped Mason, the event transported the entire community back in time.

Gina Arens is a longtime member of the Mason Historical Society and one of the many volunteers who work to preserve the town’s history and share it with the public. She said that the society’s mission goes so far beyond just collecting artifacts- it’s about the bigger picture.

“Our mission is to promote the history and heritage of Mason, and to make it accessible to everyone,” Arens said. “We want people to see that history is real stories about the people who lived here, and that [there are] lessons we can learn from them.”

Arens said that the Cemetery Walk is one of the many ways that the society tries to make Mason’s history engaging for its residents.

“This event has always been about more than fundraising,” Arens said. “It’s about connecting people to the history that happened right here in our own community. When people hear these stories acted out in the cemetery, it sticks with them.”

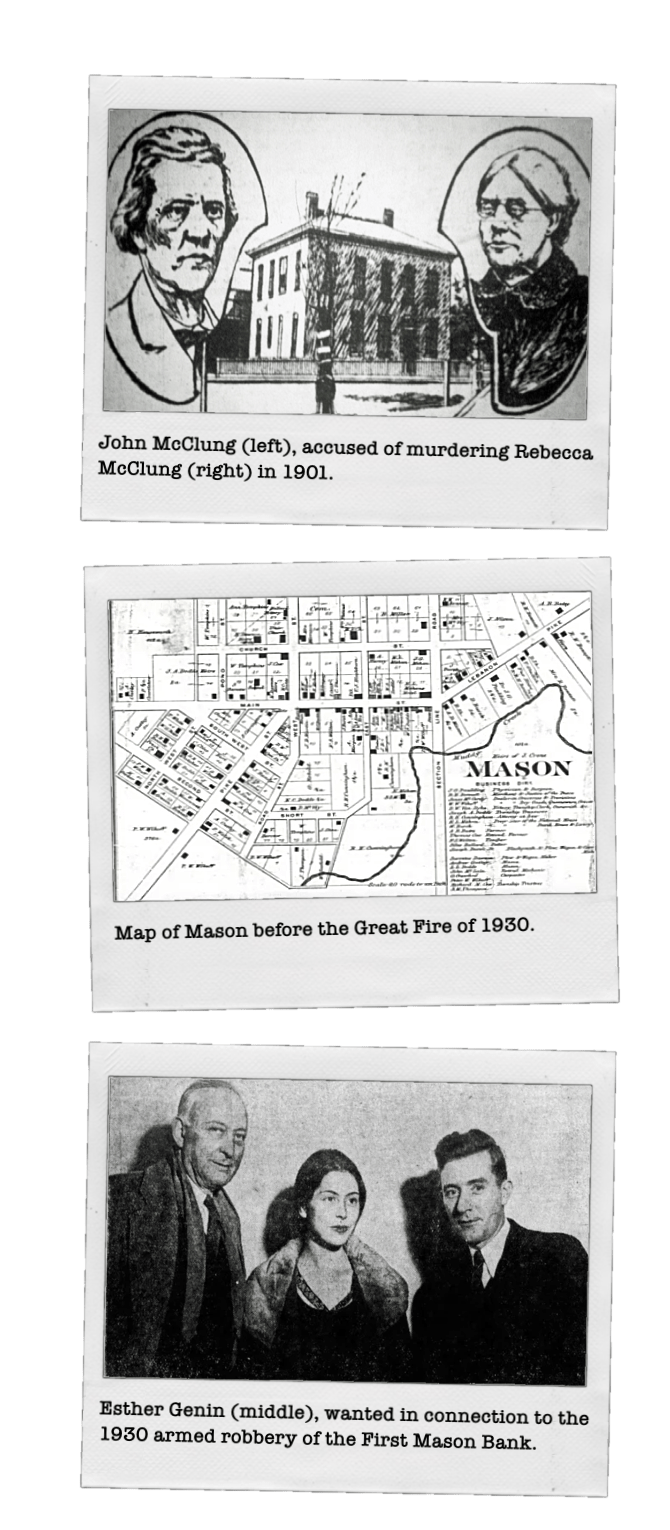

One of the most unforgettable tales told at the walk is the murder of Rebecca McClung in 1901, Arens said. Rebecca and her husband, John McClung, built a home that is now known as Thai Terrace, today rumored by many to be “haunted”.

“In those days, Mason had only one marshal,” Arens said. “He could barely keep up with day-to-day issues in town, let alone murder investigations. At the time, Mason was a town filled with crime. The McClung case was the kind of story that people whispered about for decades.”

Arens said according to accounts, Rebecca was killed in the early morning hours. Neighbors later testified to hearing screams from the house. Sally Basel, who lived on the first floor, rushed to get help because she was convinced something was “terribly wrong.”

“They held three major hearings in the Opera House,” Arens said. “John McClung was accused of murdering his wife, but in the end, the jury returned a complicated verdict, ‘not guilty in the manner in which he was charged.’”

Arens said that in terms of reflecting on that verdict, the Cemetery Walk shed light on the case for visitors.

“Visitors followed the story of the key witnesses and the coroner’s report,” Aarons said. “In our reenactment, the people watching the walk found John McClung guilty with the evidence they saw, even though the historical record shows he was ultimately found not guilty.”

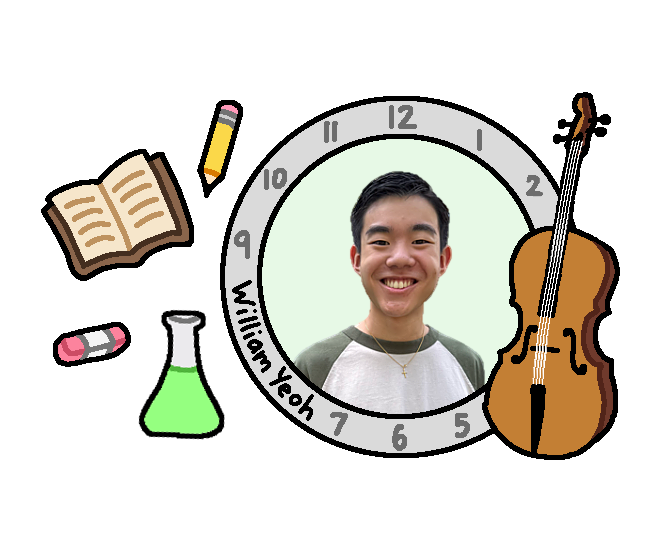

Among the other tragedies revisited at the Cemetery Walk is the Great Fire of 1930, which wrecked much of downtown Mason and led to the loss of many historic buildings.

“The fire nearly destroyed Mason,” Arens said. “It burned through a huge section of the east end, and people thought the whole town was going to be lost. The accounts of it are chilling.”

At the walk, actors portrayed George Kohl and Joseph Davis, two men who represented opposing sides in the town’s debate over waterworks, an issue that became especially urgent after the fire exposed how unprepared Mason was to fight such disasters.

“George was adamant that Mason needed a town water system,” Arens said. “Joseph disagreed, arguing it was too expensive and unnecessary. And then came the fire. Suddenly, Mason was fighting to survive with resources, and that argument about waterworks became life-or-death.”

Arens said people described it as chaos, as flames passed from building to building, residents struggled to respond.

“Residents formed bucket brigades and passed water from wells in an attempt to stop the fire,” Arens said.“ The air was thick with smoke, with people running everywhere with their children and valuables for safety.”

Arens said that while the fire was a tragedy, it shaped Mason into what it is today.

“The fire was a turning point,” Arens said. “People realized Mason couldn’t stay a small farm town forever. The fire forced [our] progress.”

The Cemetery walk also told the story of Mason’s biggest heist, the 1930 armed robbery of the First Mason Bank. Arens said the story is told through the eyes of Ollie Compton Scott, a young bank teller who faced the robbery firsthand.

“Ollie was only in her twenties,” Arens said. “Imagine being that young and suddenly staring down the barrels of guns at the place you work.”

During the walk, a performer takes on the role of the bank teller, portraying her experience for visitors, from the initial break-in to the rushed exit of the robbers.

“We have someone acting as Ollie, and they really convey the fear she must have felt. People can understand what it was like when the robbers barged in and how panicked Ollie was.”

The cemetery walk is one way the Mason Historical Society works to keep the past alive for younger generations. For students like sophomore Elisa Hefferan, volunteering with the historical society has been an eye-opening experience.

“I think people my age sometimes don’t realize how much history is in their own town,” Hefferan said. “We always hear about history in school, but when I started volunteering, I realized Mason has its own amazing and interesting stories,” Hefferan said. “Like all the crimes they talk about in the cemetery walk.”

Hefferan said she spends her weekends helping organize archives and photographs at the historical society’s museum, which has given her a new perspective.

“It’s really cool to see how things have changed,” Hefferan said. “Even something as simple as an old letter can tell you so much about what life was like back then. That’s why I really like volunteering there.”

Rachel Pansing, a teacher at Mason High School (MHS), said events like the Cemetery Walk are a chance to connect the classroom with lived history. Pansing teaches a newer elective brought to Mason called Queen City Studies, which covers Mason and Greater Cincinnati’s past.

“When I heard about the Cemetery Walk, I knew I wanted to tie it into my class,” Pansing said. “I think it’s important for students to know the background of their own home, and that is the focus of my whole class.”

Pansing said she began offering extra credit to students who attend the walk and reflect on what they learned.

“This class is about helping students see that history isn’t only about presidents or wars,” Pansing said. “It’s more about their own streets and the people who lived here before them.”

For Arens, Hefferan, and Pansing, the cemetery walk is more than an event; it is a reminder that history is alive and relevant.

“These aren’t just old headlines,” Arens said. “They are the stories of people who built this town and who suffered and overcame. When you hear their voices in the cemetery, it makes you proud to call Mason home.”