Coding for a Passion: Video game development combines creativity with technology

Aditya Thiyag | The Chronicle

While most teenagers opt to spend their afternoons playing video games, others have stayed up to design games of their own.

A majority of popular video games are “AAA” games, which are any games released by game developing companies with a larger budget. Since most people do not have access to such a budget, smaller-scale developers, high schoolers included, traditionally develop and publish independent titles, traditionally referred to as “indie” games.

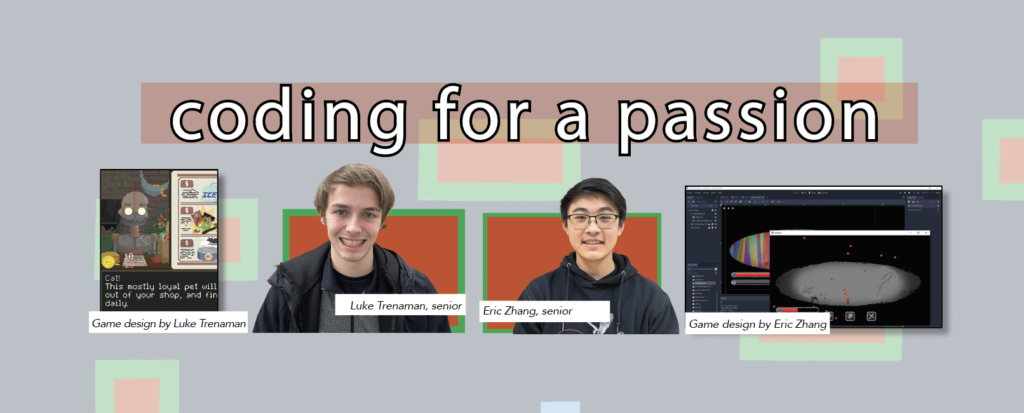

Senior Luke Trenaman has been coding indie games for eight years. He said that his coding exploits started as a result of his older siblings and that they introduced him to a basic coding software known as “Scratch”. Trenaman also said that the communal nature of the platform is what kept him engaged with game development to this day.

“On Scratch, you could look at the games other people had made and the code for that,” Trenaman said. “It was cool because I could share the games I made with people on the website and they gave me feedback on them. So I had fun using it in third or fourth grade, even though my games were really bad.”

With his initial games serving as prototypes, Trenaman said that he used his knowledge and love for playing video games to code future games. By combining his knowledge with the feedback he received from his friends, Trenaman was able to rectify mistakes made in his debut title, Snake Maze, which he said was largely considered to be “unforgiving” and “lengthy.”. Trenaman said that he then sought to make his games contain a “gradual difficulty curve” to increase the professional quality of his games, taking inspiration from his favorite games.

“After the feedback that I received on Snake Maze, I tried to decrease the overall length of my games.” Trenaman said, “I modeled that based on a game called Cuphead, which [gives you] checkpoints and it tells you how far along you got. So in [my] new game[s], I made a progress bar to motivate people to keep playing.”

Trenaman said that he quickly learned what an arduous task coding games individually was. Even for indie games, he found that collaboration was a vital part of the game-making process. Trenaman sought designated individuals, seniors Jessica Li and Meriele Green, to help manage the art direction, “website architecture”, and other aspects of his games to reduce his workload. During this pursuit, Trenaman met Senior Eric Zhang during the 2019 Hackathon where the pair developed a game together.

Zhang said that as a result of continuing to collaborate with Trenaman since then, his game-making process evolved drastically to be more spontaneous.

“Each project is very different, but my [game making] process is less structured.” Zhang said, “It [involves] a lot of trial and error. If I build something and like it, I’m going to build [more of] it and just see what happens. And I [keep] trying new things until it crashes and burns.”

As someone seeking to make game design his future career, Zhang said that his biggest worry with his experimental development style was that he would quickly exhaust all possible game ideas. To combat this rapidly growing fear, Zhang said that he took to his favorite video games on the market and attempted to notice key patterns between them that made them unique and innovative and incorporated those aspects into his brainstorming process. He said that he eventually discovered that a lot of the games being released were “essentially the same core game” but felt different due to one “simple” twist.

“For example, Super Mario Odyssey took Mario and made it open-world like The Legend of Zelda, but it was really good.” Zhang said, “The tiniest spin can turn anything from a straight copy of an original idea to something that can be vastly different and interesting.”

Unlike Zhang, Trenaman said that he is reluctant to make video game design into a full-time career. He said that the competitive nature of the gaming industry does not mesh well with his approach to game development, but he still plans to keep pursuing it.

“For someone who can get burnt out while making games, [coding] them serves as a good hobby.” Trenaman said. “It took me two years to make Snake Maze [because] I’d frequently take a three-month break where I did not code at all. So I don’t feel like I could commit consistently to working on making games because gaming companies tend to overwork you.”

Despite not wanting to professionally develop games, Trenaman said that game design still led to new and exciting opportunities. He used the extensive coding and design knowledge he accumulated through game design to design a new student activities website for Mason High School (MHS).

Trenaman said that he stumbled upon the opportunity in the process of trying to complete an Honors diploma, and since he thought the original website did not contain much “style”, his development process was heavily influenced by the visual flair he picked up through coding games and websites while continuing to make it usable.

“Making games teaches you how and where you need to put things on a screen to make it intuitive,” Trenaman said. “With web design, it’s the same thing. You have to create an interface where the information is easy to find and it’s easy to use. But I still wanted it to have my programming style.”

The skills learned from the game development process were not strictly tied to those coding. Zhang said there are numerous facets of developing a game and not all of them revolve around computer science. He also said that with the rapidly growing state of the game industry there is no shortage of job opportunities available for individuals looking to apply their skill sets in a real-world context.

“If you want a good game, you need people to write dialogue, to compose soundtracks, to draw characters, and more,” Zhang said. “ There are so many available opportunities across a wide spectrum of talents and even if you don’t know how to code, there’s still a place for you in game design.”