Biracial students grow to accept their identities

Kaelyn Rodrigues | Managing Editor

In a society bent on labels, students who fail to fit into just one category seek to resolve and accept their biracial identity.

Senior Chandrika Vasan, who is half-Indian and half-white, grew up in a town with “no people of color around” before relocating to Mason when she was in fifth grade. Vasan said she went through a culture shock after moving to Mason and experiencing the diversity of the city, which ultimately led to her growing to “accept [her] identity”.

“I struggled more with [my] identity as a kid than I do now,” Vasan said. “Growing up being the ‘different’ one was a tough experience, but going from being the different one to being somewhere as diverse as Mason has definitely changed how [I] view [myself].”

Vasan, whose father is from South India and mother is from Indiana, describes herself as “white-passing”. While attending Indian functions, Vasan said she was oftentimes “the only white person there”. Similarly, at gatherings with her mother’s side of the family, Vasan also felt ostracized, as if she was “the odd one out” because of her Indian heritage.

“I personally don’t look Indian– you can’t really tell unless you’re looking for it,” Vasan said. “I definitely had trouble fitting in with other Indians, but I also wasn’t white enough to fit in with the white people. It’s like I had to be one or the other, but I couldn’t choose because I’m both.”

Although she grappled with her identity as a child, Vasan now sees being biracial as an advantage that has allowed her to develop a unique cultural perspective and gain a broader understanding of how the world works.

Vasan said she is grateful to have grown from the mindset of wishing she could be fully Indian or fully white that she had while growing up. “People who are biracial often try to fit into one side of their identity, which is something I’ve always struggled with,” Vasan said. “A big point of growth for me has been growing up and accepting myself. I’m a mix of both [races], and that’s what makes it so interesting.”

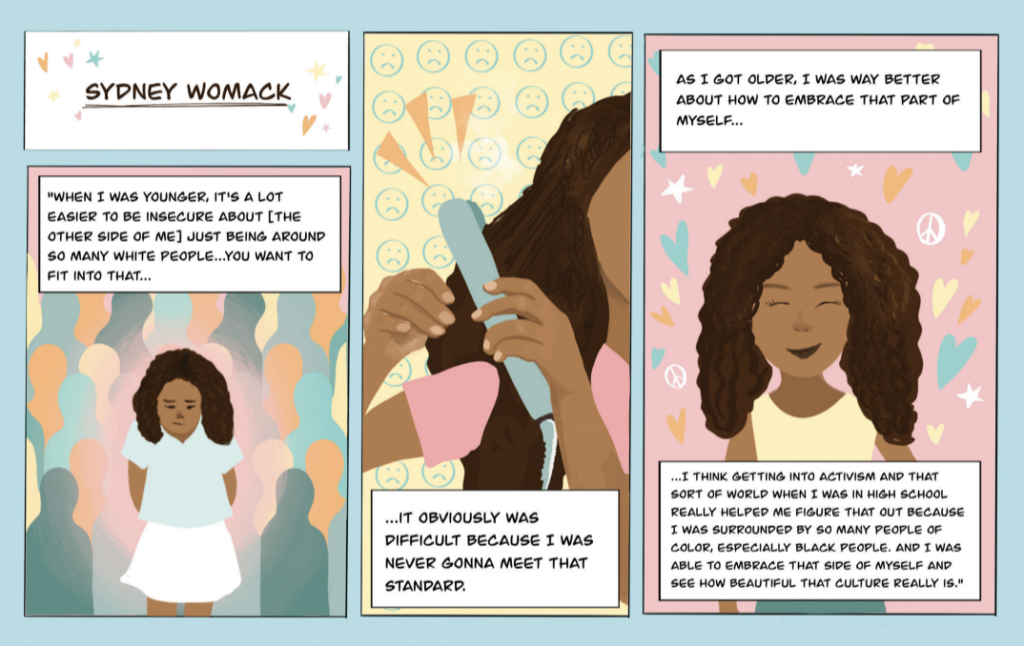

Senior Sydney Womack has seen how the presentation of the two sides of herself ebb and flow depending on her age, circumstance, and mindset. For instance, when she was younger, being around a predominately white crowd reflected an insecurity upon herself that she was not white enough. Among other practices, she recalled straightening her hair for what she considered “all the wrong reasons.”

“When I was younger, it’s a lot easier to be insecure just being around so many white people,” Womack said. “You want to fit into that. It obviously was difficult because I was never gonna meet that standard.”

On the other hand, when she is around her dad’s side of the family, she contemplates both her identification with being black and the privilege that comes with being half-white. “It can be kind of ostracizing,” Womack said, in reference to this tension that she feels internally and witnesses externally.

“There’s still definitely a bit of a disconnect there, just because I don’t fully understand that experience,” Womack said. “It’s very clear to them that I [have] more privilege than they do because of that. So I think it makes it hard to fully see me as one of them, which I understand. But it’s also difficult because I see myself very much as a part of that group.”

Understanding these differences and considering how her perspective shapes the distinct qualities and uniqueness of her voice has been crucial toward acceptance of the divide within herself. Womack credits her involvement with social justice as a community that pushed her to reflect on the parts of herself she previously tried to hide.

“Getting into activism when I was in high school really helped me,” Womack said. “I was surrounded by so many other people of color, especially black people. And I really was able to just embrace that side of myself and see, like, how beautiful that culture really is — I should not ever be ashamed of that.”

Now as she continues her foray into the social justice circle, she appreciates the meaningful diversity and powerful impact that it provides. Womack also understands, however, how her biracial identity sets her up to be both inextricably linked to this community and an ally that should stand back and listen when needed.

“It’s trying to not overstep my boundaries when it comes to my blackness and trying to make sure that I am always understanding that I do have a lot of privilege being biracial,” Womack said. “I don’t want to overstep those boundaries and try to speak over people who are fully black and have a different experience than I do. That’s probably the biggest thing for me.”

Reflecting on her experience when she was younger and far more insecure about her place in the world, she wished that someone would have helped shed light on her struggles. Womack said that she would have told her past self to focus less on the presentation of her identity and more on just living and growing up, letting her identity shape itself in the process. “[Don’t] be so worried about your identity when it comes to your race, because I don’t think that should be the biggest factor for you,” Womack said. “And that it’s important to just focus on yourself as an individual and what you like and not constantly be worrying about how that relates to your race.”

While Vasan and Womack have distinctly different experiences, the journey to find their place in the world has been difficult but rewarding for both of them. It is an identity that Womack feels is best understood by her biracial peers.

“I think that we all kind of share that experience of not really having a set place in the world because the world is very centered around racial identity,” Womack said. “And so when you do not fit into one category, it can be really hard to find your place. It’s very easy to connect with other biracial people and to find other people who can understand that experience.”

Graphic by Rachel Cai